Mictecacíhuatl, Goddess of Death

Origins of Día de Muertos

The cult of death has been an essential part of all civilizations throughout history. However, nowhere else in the world commemorates death in such a deep-rooted, mystical and joyful way as Mexico does. While in other cultures death is commemorated, in a solemn way, we, Mexicans, are filled with joy and rejoicing, with flowers, costumes, food, drinks and songs, to make our deceased feel how much we continue to love them. On the first and second day of November, the most unique and emblematic Mexican holiday is celebrated, which has become part of its identity as a nation: The Day of the Dead.

We Mexicans believe that if we remember the dead with affection, gratitude and joy, they will not cease to exist in our hearts. In other words, on the Day of the Dead, it is not mourning, but quite the opposite, it is a celebration of life, where the dead return to live together, even if it is for a couple of days, in all the houses, cemeteries, streets. and squares of Mexico.

“Solo con tu amor yo puedo existir” (Only with your love I can exist). Recuérdame (Remember me) Original Song Coco, Pixar, Walt Disney Records, 2017. Written by Robert López and Kristen Anderson López.

The Frenchman André Bretón (1896-1966), founder and main exponent of surrealism, once mentioned that the love he felt for Mexico was based, among other things, on the power that Mexicans have to reconcile life with death.

Death in the Aztec Empire, The Arduo Journey to Mictlan and The Origin of the Day of the Dead.

The Aztecs, also known as Mexicas, inhabitants of Tenochtitlan, today Mexico City, had their own way of interpreting the world, life and death. For them, the cult of death was a fundamental element of their culture and traditions. The beliefs of the Mexica were based on a cyclical vision of the universe and therefore, they saw death as an inherent part of life. In this way, the festivities in relation to death took place at the beginning of the harvest, since for them death was not an end, but rather the possibility of cyclical renewal.

Before the arrival of the Spanish, the Mesoamerican peoples did not know the concept of hell and paradise, since for them death did not have the distinctive moral connotations of Catholicism. In this way, in the Aztec empire there was no concern about death, since for them the important thing was the way one had died and not how one had lived. For the Aztecs, they believed that the final destiny of souls was determined solely by the type of death they had had.

The underworld reserved for those people who had died naturally was known as Mictlan, kingdom of Mictlantecuhtli and Mictecacíhuatl, god and goddess of death. To reach Mictlán, the souls had to go through difficult tests for 4 years, in 9 different scenarios or levels, in a kind of purifying journey, and in this way reach eternal rest. Furthermore, the Mexica people believed that to guide the soul during this arduous journey it was necessary for the deceased to be buried next to a Xoloitzcuintle dog, which served as a guide during its journey. Apart from their canine companion, in the earthly world, the relatives of the deceased organized a series of festivities and offerings in order to also guide the soul to its final destination, this being the historical origin of the Day of the Dead festivities, as we know them. currently.

However, Mictlan was not the only place where the souls of the dead went, since evidently not all of them died naturally. There were three other underworlds: Omeyocan, Chichihualcuauhco and Tlalocan.

Omeyocan. Paradise of the Sun, Kingdom of Huitzilopochtli, God of War. Souls who had died in combat arrived at this place. Interestingly, these included women who had died in childbirth and captives who had been sacrificed. Arriving at Omeyocan was a privilege, since during their stay they were going to rejoice in perpetual songs and dances, and then return to the earthly world in the form of birds as a reward for their sacrifice. Chichihualcuauhco. This paradise was reserved for the souls of deceased children. According to Mexica beliefs, in this place there was a huge tree from which milk dripped and in this way the children were fed. The souls that reached this underworld were also considered privileged, since they were destined to return to earth when the human race became extinct and thanks to them life would be reborn again. Finally, Tlalocan or paradise of Tlaloc, the God of rain. This destiny was for souls who had died a water-related death, in other words for people who had died by drowning.

Día de Muertos Altars

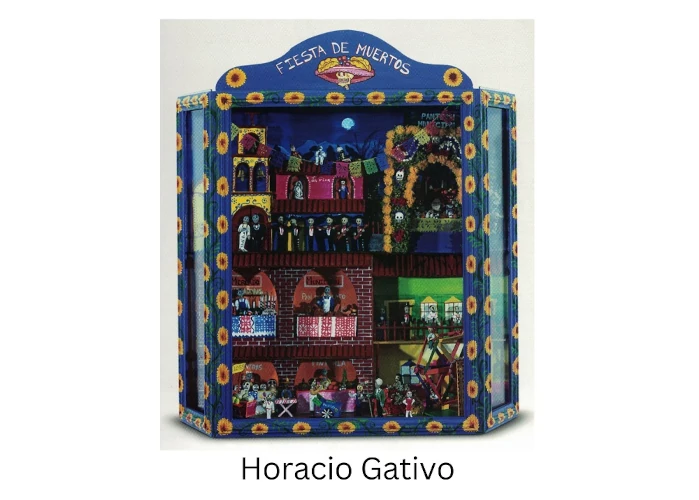

According to the beliefs of the Aztec civilization, so that the souls of the dead could begin their journey to reach Mictlan, the living were responsible for guiding them through rituals. Firstly, just after dying and before the body was buried, it was covered for four days, with personal objects that belonged to him while he was alive, which he might need during his journey to the underworld. Likewise, the body was symbolically fed with delicacies, drinks, and its favorite foods. After four days the body was buried and in this way its soul began its journey. Certainly, this tradition was not only focused on helping souls descend, but also served to facilitate the grieving process of family and friends.

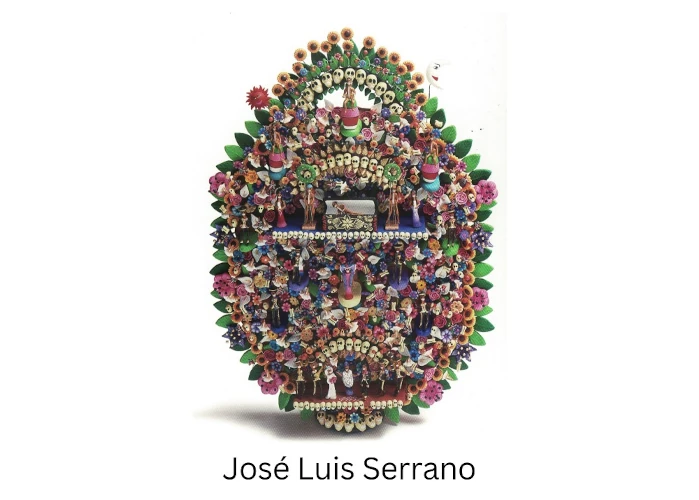

Today, Day of the Dead altars include all types of elements, from the most common such as papel picado, candles, food, water, sugar skulls and crucifixes and rosaries, to much more personal objects such as handwritten messages and photographs. Furthermore, the Day of the Dead offerings serve as vehicles for the dead to come to life, even if only in a symbolic way, and for this reason it is common to find objects that the dead enjoyed when they were alive, such as their favorite books, objects that they collected, or even alcohol and cigarettes. The Day of the Dead offerings help the deceased visit us, through our memories, by invoking their way of being, their virtues and their tastes, as a symbol of affection and love. Another element commonly used in Day of the Dead altars are Cempasúchil flowers, which with their strong aroma and vibrant color have been used from pre-Hispanic times to the present day, to guide the spirits on their return home.

Offerings to the dead in Christianity are sumptuous and gray places, related to veneration and prayer. Otherwise, the Day of the Dead offerings are an explosion of shapes and colors, so characteristic of Mexican culture.

Día de Muertos, Halloween and Consumerism

Halloween, Consumerism, and The Day of the Dead.

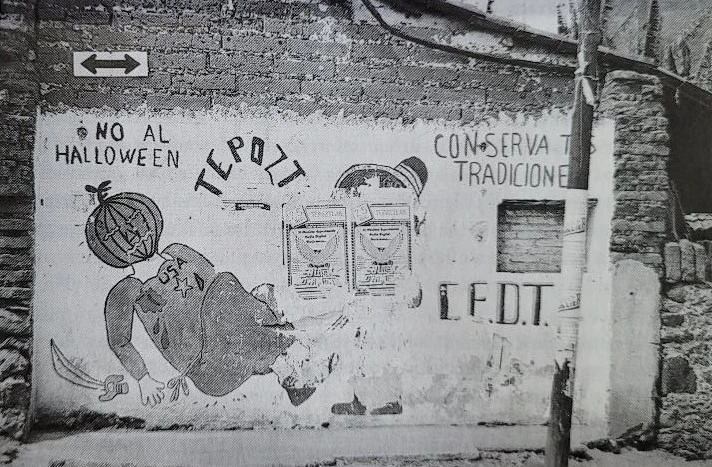

Some people ignorantly confuse the Day of the Dead with Halloween, which is why it is necessary to distinguish between both celebrations.

The Halloween festivities are born in Northern Ireland rituals, which commemorate the end of the harvest season and the beginning of the Celtic year. On Halloween, death is distorted as a kind of invasion of fearful beings, such as ghosts, witches, or monsters. However, on the Day of the Dead there are no scares of any kind, but on the contrary, in Mexico we welcome the dead in a fun way, with dances, music and colors.

Unfortunately, Halloween has been commercialized to such a level that one cannot perceive this celebration without relating it to seasonal disposable merchandise products that end up in the trash after one use. On the contrary, the Day of the Dead celebrates costumes and altars, which, more than with money, are made with a lot of creativity and imagination.

Some Mexicans fear that the Halloween holiday will take the place of the Day of the Dead; However, I do not think this will happen, since this holiday has a very deep cultural roots, which has been spread very recently internationally, in films such as James Bond 007, “Spectre” and Disney’s “Coco”. In any case, it is our job to disseminate our traditions or customs, so that they remain alive, and for this we must educate the new generations. One cannot forget that The Day of the Dead is part of the Mexican national identity.

In a ceremony held in Paris in 2008, UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) distinguished the Day of the Dead holiday as a “Masterpiece of Oral and Cultural Heritage.” Intangible of Humanity”. The decree says: “… one of the most relevant representations of the living heritage of Mexico and the world, and as one of the oldest and strongest cultural expressions among the country’s indigenous groups… That annual meeting between the people who celebrated by their ancestors, performs a social function that recalls the place of the individual within the group and contributes to the affirmation of identity.”

In other words, for UNESCO, the Day of the Dead is one of the richest cultural representations, not only in Mexico, but in the entire world. For this reason, it was worthy of being included in the list of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity, in order to be safeguarded. However, it is our responsibility, not only as Mexicans, but as members of the human race, to distinguish the Day of the Dead festivities as originating in Mexico and in this way preserve them for what they are: a cultural treasure of Mexico for the world.

The Cempasúchil Flower

One of the most significant elements in the altars and offerings of the Day of the Dead, as symbolic as the sugar skulls, the papel picado and the bread of the dead, is unquestionably La Flor de Cempasúchil.

This flower grows in autumn, after the rainy season, and its life cycle coincides with the Day of the Dead celebration, the first and second day of November.

Flower Originally from Mexico, the Nahua roots of the word Cempasúchil come from the fusion of two words. The first, Cempoal which means 20 and the second, Xóchil, which means flower or petal. That is, Flower with 20 petals.

Pre-Hispanic civilizations believed that intense orange and yellow petals guarded the sun’s rays, and their fragrance had the ability to attract even after earthly life. For this reason, it is customary to form paths with this flower, since it is believed since ancient times that its intense colors and strong aromas guide the souls of the deceased to the altars that their loved ones have made for them.

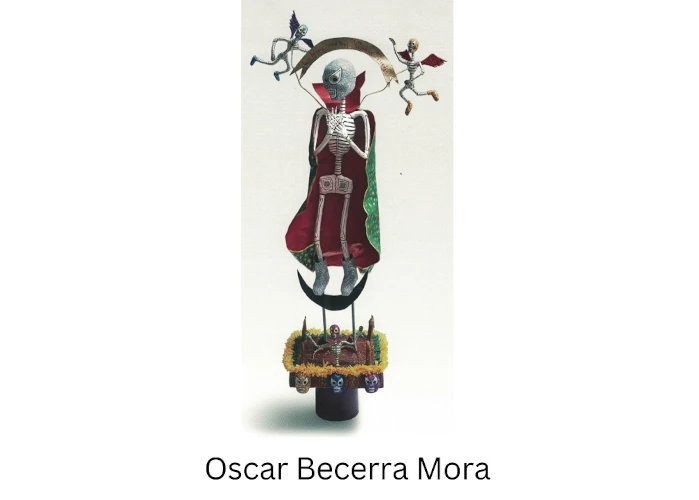

Death, an everyday occurrence

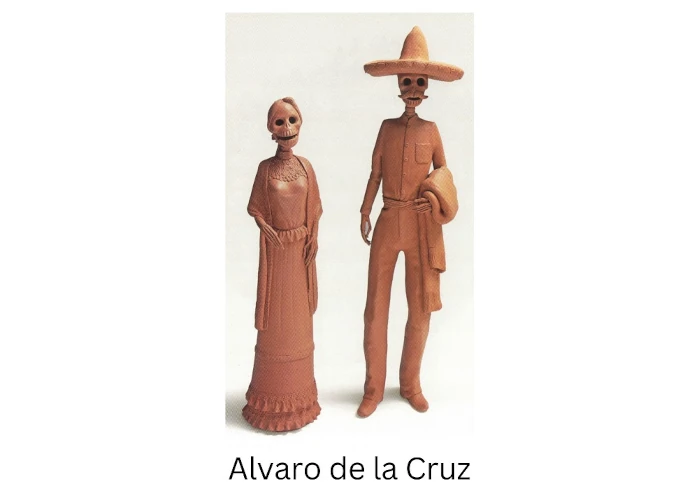

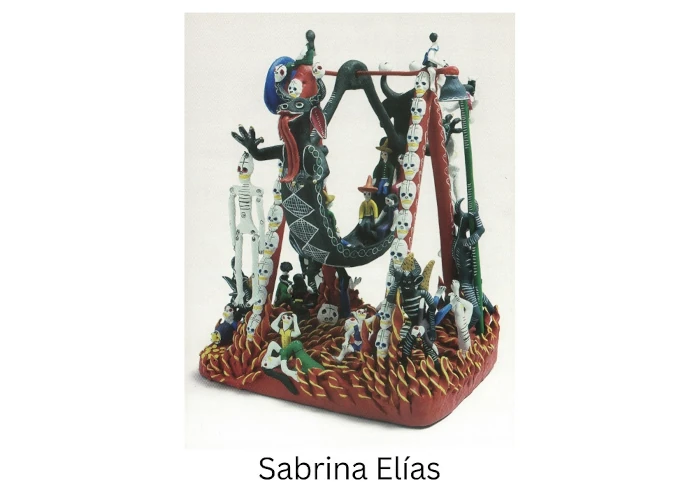

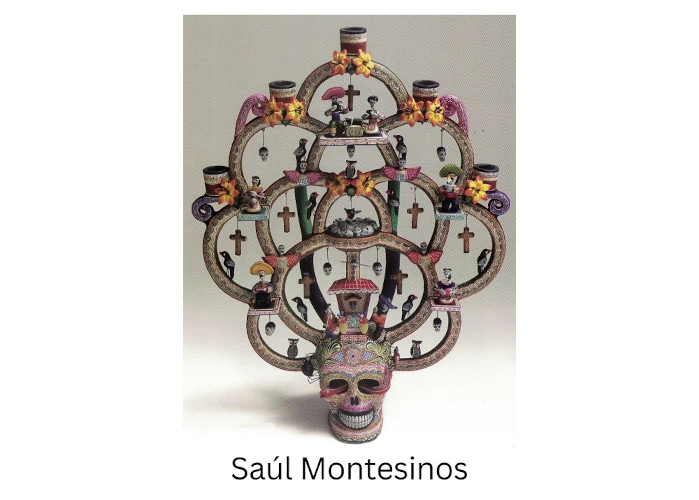

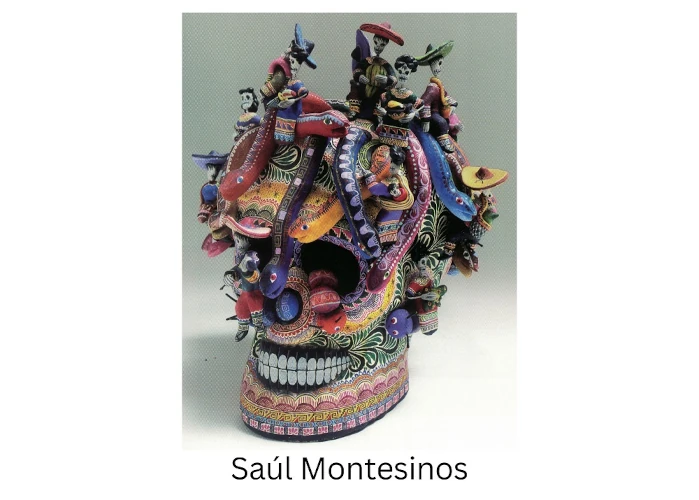

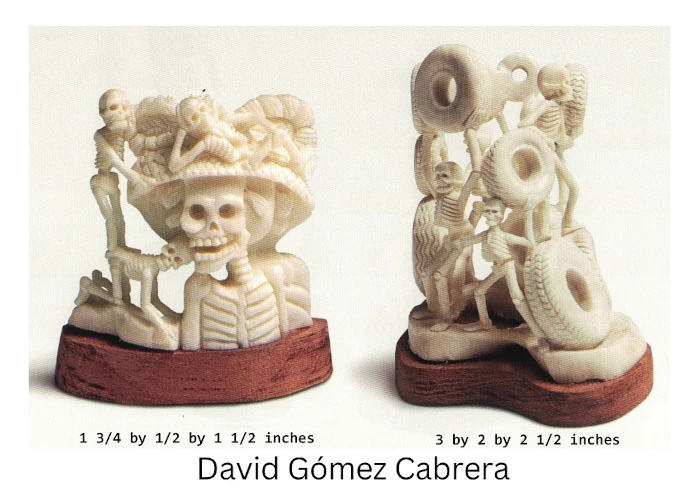

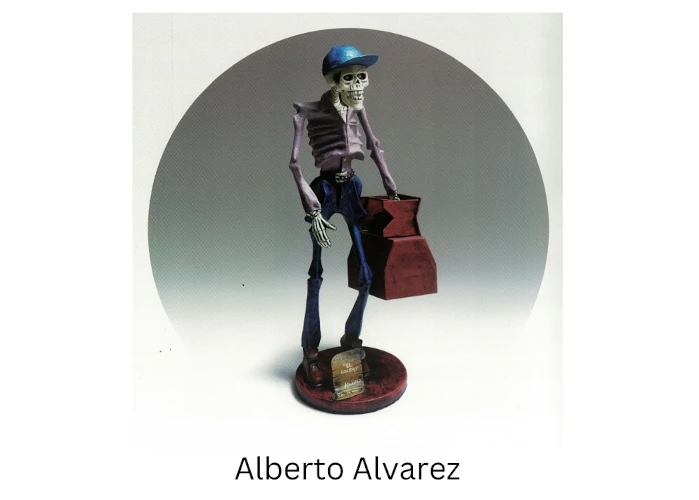

Within current popular art, death is presented without the majestic grandeur of pre-Hispanic sculptures and without the tragic premonition of its Spanish equivalents; It is a conception that is nourished by the satirical occurrence, which provokes an ironic smile; Death has stopped being taken seriously, a death with human traits, the friend or “compadre” with whom we allow ourselves to play a joke. Death in Mexican Popular Art. Elektra and Tonatiuh Gutiérrez, Artes de México, Number 145, 1971. page. 75

An element that distinguishes Mexican culture from that of other countries is the relationship that Mexico has historically had with the concept of death. Since pre-Columbian times, we have never relegated or feared death, on the contrary, we have related to it in a direct and sometimes humorous way. It is well known, in Mexico, it is impossible to enter a fair, shopping center, restaurant or school without seeing the emblematic skulls everywhere.

The Mexican has a deep-rooted link with death, its festivities, customs and artistic manifestations say it. For example, it is common to see parents give their little children sugar skulls with their name written on their foreheads, so that they eat it, in a kind of communion, as if it were the most normal thing in the world, and skeletons also occupy an important place among his toys.

While for the European the mere mention of death is considered taboo, the Mexican has been familiar with this concept from an early age.

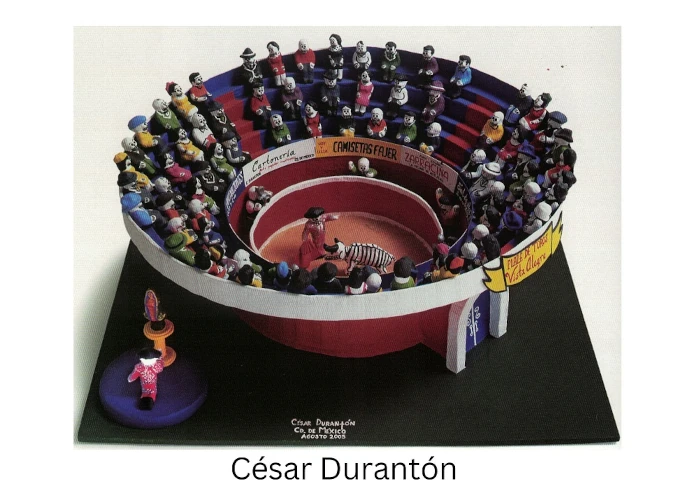

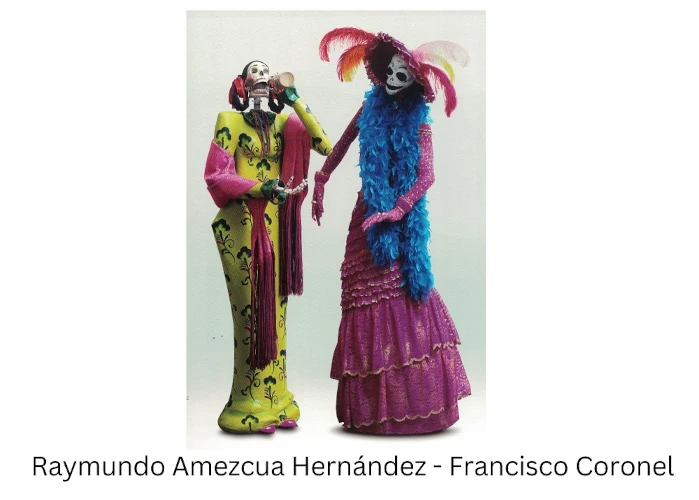

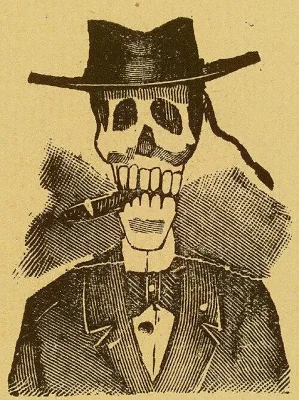

Death has been a universal theme of artistic expression in all the great civilizations; however, in no culture has this concept been represented as it has been done in Mexico. Thanks to the illustrations of the engraver José Guadalupe Posada, the skull, or skeleton, has become one of the most relevant and recurring themes in popular art. The skulls, in Mexican popular art, are characterized, not by appearing to be dead, but quite the opposite, they represent interactions in scenes of daily life. The skull interacts in all kinds of circumstances, such as parties, street fights or love pleas, characterizing all kinds of characters, or in this case skulls, from the famous catrina, to bullfighters, mariachis, and sirens. Mexican folk art, through its skulls, invites us, in a very sarcastic way, to laugh at our inevitable end. What can be said about two dolls, which represent a couple at their wedding and are actually a couple of skeletons?

Inevitably, these skulls, so everyday, indifferent and free of anguish, lead us to wonder if they really are venerations of death or celebrations of life. As Nobel Prize Winner for Literature, Octavio Paz, said: “The cult of life, if it is truly profound and total, is also a cult of death. Both are inseparable. A civilization that denies death ends up denying life.

Porfirio Díaz and his time

Mexican Revolution

José Guadalupe Posada

José Guadalupe Posada and His Time

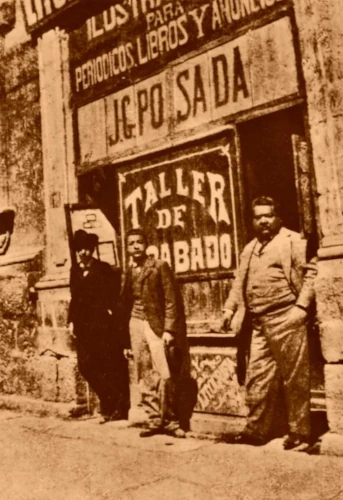

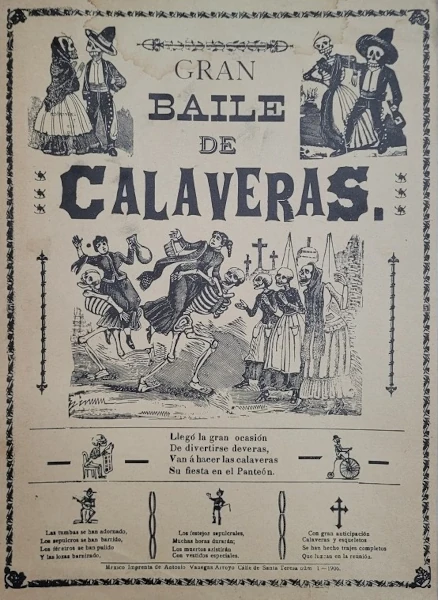

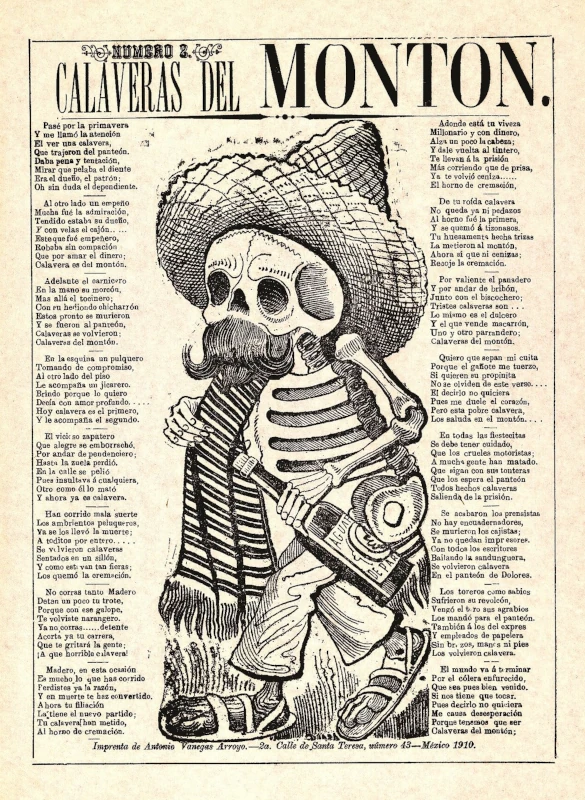

Without a doubt, one of the greatest exponents and defender of nationalist themes in Mexican art was the draftsman, lithographer and engraver José Guadalupe Posada. Born on February 2, 1852 in the city of Aguascalientes, Posada was one of nine siblings, sons of a baker, who with his burin on a metal plate made more than 15,000 engravings, becoming the most important chronicler and denouncer of life. everyday life in Mexico at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. José Guadalupe learned different engraving techniques from a very young age and worked in a large number of publications, magazines and newspapers throughout his life, however, it was with the editor Antonio Villegas Arroyo, in Mexico City, where Posada created his most famous and influential engravings. As unfortunately often happens with great talents, he died in total poverty, in a neighborhood in the popular Tepito neighborhood, in Mexico City, in 1913, and since no one claimed his body, he was buried in a common grave. . Being cruelly forgotten, a humble tombstone on his grave did not coincide, but paradoxically, but it was this same theme, death, that immortalized him. Furthermore, despite being one of the most influential artists in the history of Mexican art, only two photographs of Posada are known, the most famous being the one that appeared on the cover of the “Hoy” Magazine published in 1952. , where he poses in front of his workshop.

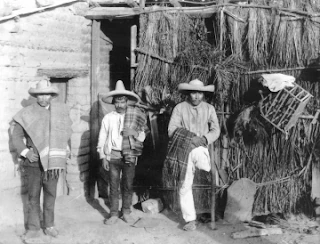

To understand Posada’s work, one would first have to analyze the Mexico where he lived. José Guadalupe was born right in the middle of the 19th century, in a Mexico that had just gained its independence a little over three decades ago and where the majority of the population could not read or write. Consequently, the engravers of magazines and newspapers, at that time, took on the task of disclosing facts of national importance using caricatures as a trigger for opinion and not the written word. In this way, it was extremely important that the journalistic illustrations, such as those in which Posada depicted his engravings, were expressive, simple and comic enough to attract the attention of the illiterate public. José Guadalupe graphically exposed Mexican society: characters of the moment, artists, politicians, and he used death, or rather skulls, as central protagonists instead of people in life, thus consolidating the Day of the Dead in their interpretations of everyday life.

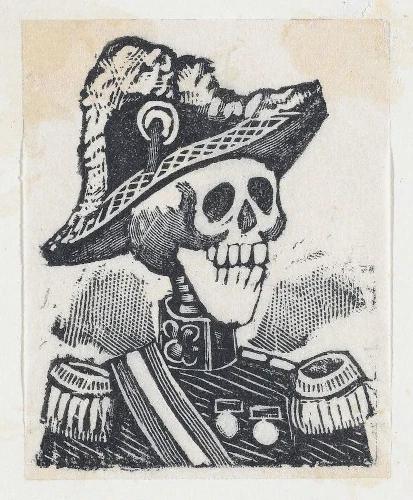

The vast majority of Posada’s engravings were made during the Porfirio Díaz dictatorship (1884-1910), a period known as the Porfiriato, a period in which there were great technological advances and relative social peace. However, in exchange for this growth, there was a notable increase in inequality. With the motto of “Order and Progress”, Porfirio Díaz introduced telephone communication, the railways and the first automobiles began to circulate; however, such advances never reached the lower classes, sparking the Mexican Revolution and Díaz’s subsequent removal from power. Posada’s engravings evidenced the inequalities and suffering of the people, using the skull in a very ingenious way, as an instrument of social and political criticism, establishing it in the Mexican collective imagination.

During the Porfiriato, José Guadalupe Posada used his publications to denounce the excesses and claims of the political class, making a very imaginative and caricatural analysis of a society in decline.

“Surely, no bourgeoisie has had as bad luck as the Mexican one, for having had as a righteous reporter of its ways, actions and adventures, the brilliant engraver, the incomparable Guadalupe Posada”. Diego Rivera.

In fact, historians affirm that Posada was the one who best portrayed the reasons for the first armed conflict of the 20th century, the Mexican Revolution, which claimed more than one million four hundred thousand lives over a decade, firing the first bullets, of course. , allegorically.

La Catrina Garbancera

Posada’s Skull

To understand José Guadalupe Posada’s scathing criticism of the inequalities of his time, one must first analyze why he used death, or skulls, as his main theme. The famous engraver and chronicler seems to tell us in a very direct and scathing way that we all, rich and poor, have something in common: we are all going to die. In this way, José Guadalupe faithfully believes that the only revenge of the oppressed is death, since after death, everyone, privileged and unfortunate, ends up being the same, a skull. In other words, we are all, as the engraver said: “heap skulls”. For that same reason, José Guadalupe captured satirical images of all kinds of skulls, from authorities to revolutionaries, including peasants and merchants, without forgetting, of course, his world-famous garbancera catrina.

“Death is democratic, since in the end, white, brown, rich or poor, all people end up being skulls.” Jose Guadalupe Posada.

One of Posada’s most important contributions, as far as the collective imagination is concerned, was that by capturing so many skulls in such different daily circumstances, he stripped death of its characteristic religious solemnity. In other words, Posada, between laughs, used satire as a vehicle for social denunciation and at the same time changed the intimidating perspective of death, turning it into a boldly caricatured image.

Undoubtedly, the most satirical, humorous, and representative imaginary character in Posada’s scathing social criticisms was his garbancera, who embodies the decadence of the society in which I live. The name “garbancera” comes from the fact that some women of indigenous descent hid their roots and sold chickpeas instead of the popular Mexican corn, pretending to be part of the aristocracy. Likewise, La Garbancera is distinguished by her Victorian attire, with a feathered or flowered hat, gloves and an umbrella. It is worth mentioning that during the times of Posada there were very marked distinctions in the clothing of upper class people and people of the town. For this reason, the aristocracy, or whoever claimed to be part of it, wore European attire, especially French or English, and thus differentiate themselves from common people. La Catrina garbancera by José Guadalupe Posada embodies the ridiculousness of a sector of society, which self-consciously rejects what is Mexican as inferior, in favor of European tendencies, in order to pretend to be something that it is not.

Posada and Mexican Contemporary Art

José Guadalupe Posada is considered the most important graphic artist in Mexico. Furthermore, many historians believe that his work marked a before and after in what refers to Mexican art, since they consider that he was the one who abandoned academic prints, thus opening the door to a subject that was denied for centuries. : nationalism. Today, his skulls are part of the imaginary of the Mexican people, becoming transcendental elements of popular culture in all its manifestations.

Likewise, the trinity of Mexican muralism, Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros admitted, in their time, to be admirers and followers of Posada, considering him the forerunner of the nationalist movement in the arts. In fact, Orozco came to relate that as a child he would pass by Posada’s workshop on his way to school to admire his work and this influenced him to choose painting as a profession.

“Posada worked in public view behind the shop window facing the street and I would stop for a few minutes delighted, on my way to school, to contemplate the engraver… This was the first stimulus that awakened my imagination and prompted me to blur paper with the first dolls, the first revelation of the existence of the art of painting.” Jose Clemente Orozco, in 1971.

According to Diego Rivera, also a fervent defender of nationalist and popular themes, Posada personified the “prototype of a people’s artist” becoming his object of adoration.

The greatest tribute that Diego Rivera could have made to Posada, a work that catapulted the myth of the garbancera-catrina, is a 4.17 x 15.67 meter mural, which was initially in the Hotel de Prado, but after the 1985 earthquake, It was transferred to the Diego Rivera Mural Museum, in Mexico City, and is entitled “Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central”.

This mural work is a chronological-allegorical representation, from left to right, of the history of Mexico, with key figures from very different eras, such as Hernán Cortés, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Maximiliano de Habsburgo, Benito Juárez, Porfirio Díaz and Francisco I. Madero, among many others. But there he is, in the center of that mural masterpiece, a place of honor in the history of Mexico, José Guadalupe Posada, taking the left arm of his creation and the maximum symbol of Mexican popular art, of death, the catrina, his catrina, while she takes her right arm, to the children’s version of the author, Diego Rivera.

Traditional and Digital Art

,,,Paintings have been a medium of expression throughout human history, In fact, oil paintings, by means of rock pigments, have been used as early as the 7th C. However, in the last forty years, and more significantly, after the boom of the internet and more receltly the boom in artificial intelligence, there has been a substantial increase in the use of digital technologies that have allowed digital art to bloom.

Evidently, traditional art uses mediums, such as oil paintings, acrylics, and watercolors to produce art whereas digital art uses technologies such as hardware and software. However, there are certain very distinct characteristics between both that one must always keep in mind

A Sensory Experience: The most evident difference between traditional and digital art is that the first uses physical media such as oil/acrylic paintings, canvases, and brushes, instead of computer screens and styluses. In other words, traditional art can be touched, smelled, during the process of creation, and after it has been completed. This builds a connection between the artist and his work, or the person who purchased the art. IE the collector.

No Copy/Paste button: In digital art, the artist uses a stylus to “paint” on the computer screen instead of brushes and paint on canvas. This gives the digital artist the ability to create uniform, fluid, and if desired identical strokes. In contrast, the traditional artist paints unique strokes every time. In other words, there is always a unique mixture of colors and hand precision in every stroke. Furthermore, in digital art, the artist can simply “cut” and “paste” a certain element of his creation instead of going through the process of making it again.

No undo button either: In digital art, everything is done through layers that not only increment upon one another but also give the artist the ability to separate, alter, reorder, or delete a particular layer, without affecting the others, with ease. Contrastingly, in traditional art, layers keep increasing as you physically paint over them, and errors cannot be undone entirely. This restriction forces the artist to find solutions to specific situations, which ultimately makes the artist improve his o her skills.

Furthermore, traditional art is not possible to duplicate, even if it’s painted by the same artist, and this “uniqueness” is its most cherished benefit and what gives it value. The imperfections of traditional art are not only what makes it unique, but at the same time make it beautiful. Clearly, the Internet has made digital art more accessible, however, technology is a threat to originality, because digital art will always lack that human touch

In short, technology takes advantage of digital tools, such as artificial intelligence, to create art allowing for quicker production. Traditional art techniques focus on manual skills and mastery of materials, emphasizing the artist’s unique touch.

Paco Díaz Cuéllar

Contact

Threads

Tik-Tok

Twitter (X)